So the question on most marketers’ lips at the half-way stage of the Sochi Winter Olympic Games 2014 is who’s winning brand gold and who’s coming last in the multi-million dollar sponsorship stakes?

So the question on most marketers’ lips at the half-way stage of the Sochi Winter Olympic Games 2014 is who’s winning brand gold and who’s coming last in the multi-million dollar sponsorship stakes?

Well, this picture sums up the problem, doesn’t it?

An Olympic Official at Sochi with duct tape sticking it over the Apple logo of the laptop belonging to Associated Press director of international video Mark Davies. As if this pretty innocuous indirect view of an Apple logo on this laptop justifies this type of treatment?

Well, it’s bonkers really but then you need to understand the reasoning behind this extreme form Olympic brand protection.

Non-Olympic partners such as Apple are considered to be in direct competition with the official Olympic sponsors at Sochi 2014, such as Samsung that also makes laptops. But they’re not alone.

IBM Global Services (a former Olympic Sponsor) goes head-to-head with Atos Origin, Pepsi and Red Bull are pitted against Coca-Cola, DuPont versus Dow Chemical and Royal Philips against GE. It’s brand warfare of Olympic proportions!

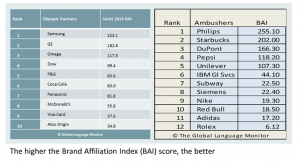

By all accounts, non-sponsors may have the edge over those that spent millions of dollars for the exclusive right to be associated with the Sochi Olympic Games 2014, according to a Report by Global Language Monitor (see Tables below).

GLM warns that the “value leak” of the Olympic brand equity could have far-reaching consequences for the Olympic Worldwide Partners.

Take this Subway advert as an example.

The fast food outlet is clearly a competitor of McDonald’s, the official global TOP sponsor but has successfully stolen a march on its rival, according to Professor Simon Chadwick at Coventry University in the UK.

The fast food outlet is clearly a competitor of McDonald’s, the official global TOP sponsor but has successfully stolen a march on its rival, according to Professor Simon Chadwick at Coventry University in the UK.

“This is obviously a deliberate strategic decision that Subway has made and it’s trying to suggest that in some way it has an association with the Olympic Games,” he observes.

Subway has kept its head down and declined to be drawn into questions about whether any link with the Olympics was intended. But clearly it can be seen to be a ‘piggyback’ advertiser riding a wave of interest in the Olympic Games but without having bought a ticket for the ride.

Whatever the ethics of doing this maybe, such a strategy appears to have paid off as Subway is now one of the brands that consumers most associate with Sochi 2014 ahead of every official sponsor, according to research by GLM.

And this won’t come as good news for the International Olympic Committee (IOC) or its global stable of official sponsors.

Ambush marketing has a long history with the Olympic Games andSubway isn’t a novice when it comes to ‘brand warfare’.

For example, during the Vancouver Winter Olympic Games 2010, the fast food chain ran ads showing Michael Phelps swimming across North America to “where the action is this winter.” Predictably, when a complaint from McDonald’s as the “official restaurant” of the Olympic Games was made, the CMO for Subway Tony Pace revelled in free publicity this created and he’s reported to have said: “My reaction to the fact that McDonald’s is upset? I’m lovin’ it!”

McDonald’s of course failed to see the funny side of this jibe having paid close to $200m for the eight-year, four-Olympics sponsorship deal that includes the Sochi Games 2014 as one of the 10 exclusive worldwide sponsors in The Olympic Partner (TOP) program. But the IOC was powerless to do anything about this.

To safeguard the investment made by sponsors, the IOC requires host nations to provide vigorous trademark enforcement.

Russia, like the UK before it, has passed draconian laws banning unauthorized use of Olympics words and symbols or any act of infringement at the event.

So duct tape is the answer to those who may inadvertently offend the brand police at Sochi as Mark Davies found out.

And the IOC insists that participating teams and athletes don’t appear in any ads during a designated “blackout period,” which this year runs until the end of February 2014.

However, it’s not a deterrent for Subway. The chain’s stable of endorsers includes former Olympians Phelps, Ohno, and gymnast Nastia Liukin, as well as current competitor Bright.

Before Phelps and Ohno retired, Subway would deploy them out of season—Phelps in winter and Ohno in summer—to avoid the blackout restrictions.

Bright’s recent appearance in the January 2014 campaign slipped under the wire as Subway ads built an association through a combination of familiar faces and generic references such as snow and ice skating and a “ring” master. Of course the Olympic Rings were nowhere in sight, but who cares?

“There’s no use of imagery, no use of words, no use of photographic or video footage so they’re not going to be subject to litigation,” muses Professor Chadwick.

Fully freighted, the cost of being a Top Olympic partner can approach $1bn (£609m) over an entire Olympiad, or the four year period between Summer or Winter Games. This cost includes the IOC rights fee, associated business development and the cost of advertising, merchandising, and the many other marketing activities undertaken by The Olympic Partners (TOP). Most of the Top Sponsors have signed multi-Olympic contracts that include Summer, Winter and Paralympics.

New Olympic festivals, such as the Youth Games, are beginning to make their presence felt on the international sporting scene. So any Olympic brand equity transferred to ambush brands can mount to hundreds of millions of dollars in value or more, says GLM.

Olympic organisers do their part to quash non-sanctioned branding by enforcing the controversial Rule 40 of the Olympic Charter that prohibits athlete and sponsor marketing for 28 days surrounding the Games which typically last 16 days. And Rule 50 provides that gear brands can be represented, but only by a 10 percent surface presence on gear or apparel used by the competitor.

Non-compliance of these rules by athletes or brands that support them could compromise an athlete’s future eligibility in the Games but this doesn’t appear to have carried any truck with snowboarders at Sochi.

Non-compliance of these rules by athletes or brands that support them could compromise an athlete’s future eligibility in the Games but this doesn’t appear to have carried any truck with snowboarders at Sochi.

Snowboard manufacturers Burton, GNU, Salomon and StepChild have seen their names plastered on nearly every high-flying snowboard at this year’s Winter Olympic Games in flagrant breach of the 10 percent rule as brand names are slapped across the bottom of boards in bright, bold colours in full view of TV cameras and spectators. And its free publicity.

The IOC put a brave face on this apparent loop hole and a spokesperson told NBC that what the snowboarders were doing was OK because “identification of the manufacturer may be carried as generally used on products sold through the retail trade during the period of 12 months prior to the Games.”

Maybe the IOC realised that sticking duct tape to the underside of a snowboard was a waste of time but there really does need to fundamental review of how these rules protect sponsors’ rights but don’t threaten to choke support for the Games in the first place and turn them into a battle ground of brand warfare where no one wins.

Recent Comments