Miracle Whip is a salad dressing similar to mayonnaise and is popular with American and Canadian consumers.

Miracle Whip is a salad dressing similar to mayonnaise and is popular with American and Canadian consumers.

Not a subject that you think would stir strong emotions? Well, actually you’d be wrong!

When marketers at Kraft began researching consumer attitudes towards the product, they found surprisingly deep emotions.

It turns out that a substantial number of people love Miracle Whip. And many can’t stand the stuff!

Back in 2011, with this consumer insight, Kraft launched a high profile US ad campaign that made a virtue out of this schism, using celebrities like Paula D fromJersey Shore and the political pundit James Corville.

Some people in the ads praised Miracle Whip’s yumminess, whereas one person said they would end their relationship if he found out his girlfriend ate the stuff and another said they would rather lick your shoe than try it.

Without a hint of irony, brand director Sara Braun proudly announced on the back of the research that Miracle Whip “is a polarising product” and that they were trying to own up to this reality.

Well, love it or hate it, social media postings on Twitter rocketed by 631% andMiracle Whip clocked up a corresponding 14% increase in sales in the process.

And this got me thinking about Ed Miliband – not because I think he eats Miracle Whip (well, I’m not sure to be honest!) but because a brand manager needs to think the same way as political campaign manager.

The point is, when a political campaign manager formulates strategy, they measure their candidate’s negative polling numbers as a matter of course – after all, knowing what share of the electorate will never be persuaded to vote for your chosen candidate is essential in determining how to approach undecided voters.

You could say it would take a miracle for Ed Miliband to remain as leader of the Labour Party by the time we tuck into left-over turkey bits on Boxing Day, but I digress..

Marketers gauging consumer attitudes have traditionally relied on ‘mean’ or ‘net promotion score’ (NPS) but over reliance on such a metric can produce a distorted picture.

For example, a brand with a middling NPS may in fact be highly polarizing, with large numbers of fervent supporters and passionate detractors cancelling each other out. Identifying these instances is increasingly important because social media gives ‘brand detractors’ ready outlets for transmitting their dislike.

This is a subject that has fascinated academics for some time, including those at Arizona State University that carried out research evaluating various brands’ polarization quotient and then examining the relationship between polarization and share price.

The researchers found that highly polarizing brands tend to perform more poorly than others, but they also tend to be less risky and exhibit relatively little variation in share price.

Whether this is good news for the Ed Miliband as he appears to be polarizing opinion within his own party remains to be seen.

But let’s get back to Miracle Whip.

In order to survive – and thrive – in such an environment – brand managers must think about adopting new marketing strategies. And this starts with an understanding of brand dispersion, a metric that measures polarization of a brand.

And as nuts as this may sound, some brand owners have boosted sales by increasing the number of brand haters.

For example, let’s take Hellmann’s Mayonnaise and Miracle Whip in a taste test. And let’s suppose that each brand manager asks three consumers to rate the products on a scale of 1 (very poor) to 7 (excellent). Let’s say Hellmann’s Mayonnaise receives ratings of 3, 4 and 5 and Miracle Whip scores 1, 4 and 7.

For example, let’s take Hellmann’s Mayonnaise and Miracle Whip in a taste test. And let’s suppose that each brand manager asks three consumers to rate the products on a scale of 1 (very poor) to 7 (excellent). Let’s say Hellmann’s Mayonnaise receives ratings of 3, 4 and 5 and Miracle Whip scores 1, 4 and 7.

On this basis, each brand has the same mean score 4, but what lies behind that mean score is an important difference.

Hellmann’s Mayonnaise scores are clustered tightly together whereas the scores for Miracle Whip are widely dispersed – it has one brand lover and one brand hater, so it’s a polarizing brand.

Outside of the taste test, there are various ways to measure brand polarization. One of the simplest ways is to look at the percentage of consumers who give a NPS of 6 or 7 and the percentage who give it a 1 or 2.

The higher the percentages of brand lovers and brand haters, the greater the polarization. That’s a metric worth knowing.

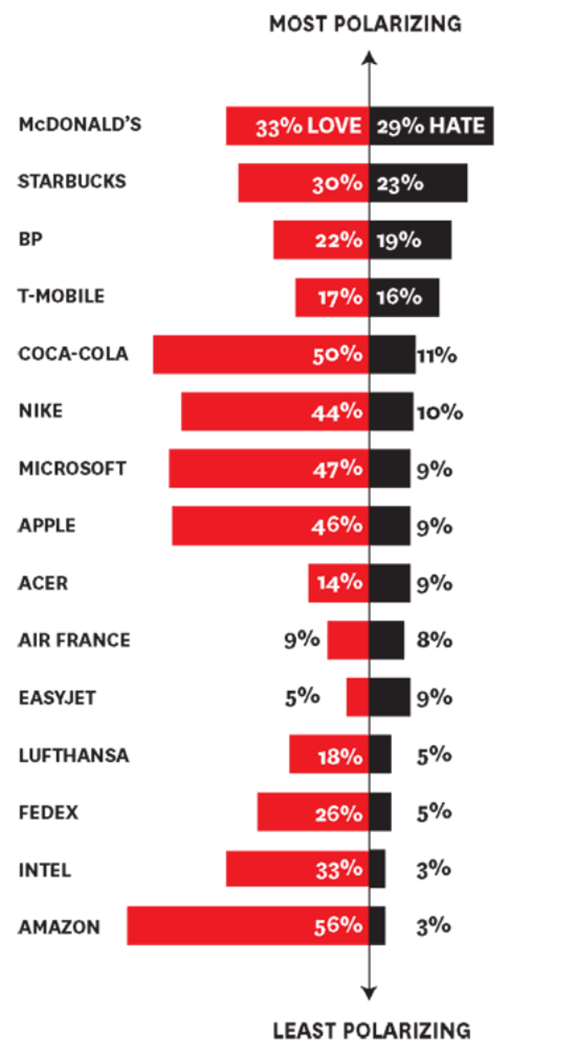

For example, according to research by YouGov undertaken in 2013, burger giant McDonald’s is a highly polarizing brand – 33% of consumers love it and 29% hate it, whereas chip manufacturer Intel doesn’t quite stir the same degree of emotions and has low polarization, with 33% of consumers loving it and just 3% hating it.

For example, according to research by YouGov undertaken in 2013, burger giant McDonald’s is a highly polarizing brand – 33% of consumers love it and 29% hate it, whereas chip manufacturer Intel doesn’t quite stir the same degree of emotions and has low polarization, with 33% of consumers loving it and just 3% hating it.

Another way to determine polarization is to calculate the standard deviation of consumers’ overall ratings.

For example, the higher standard deviations indicate greater polarization. This method is perhaps more accurate than NPS and can be especially useful when brands are rated on 3-point or 5-point scales, although according to researchers the two methods tend to produce similar results.

So back to Ed Miliband.

What should his camp do, given he’s pledged to fight the next general election campaign ‘street by street’?

Well, one way to reduce polarization is to do what most of us do when confronted with people who dislike us: try to change haters’ minds.

This is a strategy that usually feels the most straight-forward and comfortable. Brand managers who successfully deploy it reduce negative word of mouth and create a larger pool of potential buyers.

About ten years ago, General Mills’ Betty Crocker brand, best known for cake mixes, icing, and other cook-at-home dessert products was suffering because of increasing concern over obesity among the US population.

And this precipitated a shift towards low-carb products as well as criticism of food industry marketing techniques that were accused of creating a poor diet issue in the first place.

At the beginning of 2008, around 4.5% of consumers could be classified as Betty Crocker haters.

So General Mills went on the offensive and decided to take steps to reverse this polarity in opinion and in April 2009 launched a social network, MyBlogSpark to promote Betty Crocker and other brands in its portfolio and posted responses in order to diffuse bloggers’ complaints. That year, Betty Crocker became the first major brand to develop a gluten-free baking mix.

That year, Betty Crocker became the first major brand to develop a gluten-free baking mix.

It soon partnered with celiac disease foundations and launched a website for consumers, Gluten Freely (now ceased).

The brand strategy appeared to work as by May 2011, the share of Betty Crockerbrand haters had dropped to 2.8%, a fall of 1.7%.

As any brand manager will tell you, any bad word of mouth out there has a multiplier effect and research shows that negative sentiment can influence neutral consumers. Just take a look at TripAdvisor and read the negative reviews on its site if you don’t believe me.

Another neutralizing strategy and perhaps one not to be adopted by the Miliband camp is to antagonise brand detractors (too late!).

This so-called ‘Ryanair Effect’ can, in certain circumstances, reinforce the brand’s connection with its most enthusiastic customers because people often feel compelled to defend a favourite product when it’s under attack and the defence mounted by its fans can often sway neutral consumers into becoming supporters – but it’s a high risk strategy.

Alternatively, a brand manager could consider amplifying a polarizing attribute in the hope of turning a negative into a positive.

In the UK, the most famous example of this is Marmite. In fact, its own tagline is ‘Love it or hate it’ which makes a virtue of the fact it attracts such strong opinions.

In 2010, it took this a step further and launched Marmite XO – an extra strength version for those who didn’t think a dollop of the black stuff wasn’t strong enough in the first place!

In 2010, it took this a step further and launched Marmite XO – an extra strength version for those who didn’t think a dollop of the black stuff wasn’t strong enough in the first place!

Using social media, Unilever identified 30 consumers who were devotees and invited them to taste testings as well as launching its own Facebook group.

Again, the strategy pay off as the promotion generated 54,000 visits to the website and 300,000 Facebook page views, and retailers sold out of Marmite XO as soon as it appeared on the shelves.

When Strongbow saw that sales in the cider market were moving in the direction of trendy Magners cider that encouraged younger drinkers to imbibe it over ice, Strongbow could’ve decided to fight back in order to recapture some of these lost sales.

Instead, back in 2009 it decided to appeal to its traditional customer segment and focused on the fact that the drink was to be consumed all year round, not just when the weather turned hot.

Again, such a strategy paid off and sales increased by 23%, maintaining its leading position in bars and clubs in the UK. Magners of course realised that it had to appeal to a wider customer segment but sales of its cider have continued to slip by 10.3% in the first half of this year.

What each of these examples illustrates is that brand managers now have access to data they could only dream about before.

However, learning to assess and exploit brand dispersion is a natural step in this progression.

Brand managers – and political campaign managers for that matter – should avoid relying on averages; they need to dig deeper to uncover and understand the full range of attitudes, values, perceptions, beliefs and behaviours towards their brands.

Although this is especially critical for polarizing brands, all marketers should be cognizant of their brands’ dispersion and should track it over time.

Fuelled by social media, pockets of haters can quickly develop and spread, even for brands that once enjoyed universal appeal. The trick is to spot an opportunity to reverse negative polarization before it’s too late.

And that’s the Miracle Whip Factor.

Recent Comments