Pfiz er’s attempted takeover bid for British drugs company Astra Zeneca has been permanently consigned to the history books and with it the dream of creating the world’s biggest drug company that would’ve been worth a colossal $119bn.

er’s attempted takeover bid for British drugs company Astra Zeneca has been permanently consigned to the history books and with it the dream of creating the world’s biggest drug company that would’ve been worth a colossal $119bn.

So what went wrong?

Clive Rich, an expert negotiator who’s been behind some pretty big deals in his time, offers the following incisive point of view: “Whenever people negotiate the airwaves always seem to be dominated by organisational issues like price, delivery date, quantity, or valuation. We are all very comfortable hiding behind these issues. Often they are the only things that get discussed, and the parties assume that they are the only things that matter.

“But there’s usually more to any negotiation than this. Negotiation is essentially a human process, and so underlying motivations like fear, not losing face, reassurance and respect often plays a critical role. These underlying needs are frequently never discussed at all – but you can be sure that when a negotiation founders on the surface issues it’s because an underlying motivational need for one side or the other has been overlooked.”

“But there’s usually more to any negotiation than this. Negotiation is essentially a human process, and so underlying motivations like fear, not losing face, reassurance and respect often plays a critical role. These underlying needs are frequently never discussed at all – but you can be sure that when a negotiation founders on the surface issues it’s because an underlying motivational need for one side or the other has been overlooked.”

These needs often operate at a corporate as well as an individual level – the personalities involved will have their own needs and requirements which may or may not be aligned with those of their organisation, but which will need to be accommodated nonetheless.

Future MBA students will be given the task of dissecting exactly why something which looked so fantastic on paper ended up in the waste bin.

Pfizer went through the price gears fairly smoothly – from an initial offer in November 2013 that valued Astra Zeneca at $60bn, then $50 per share and then $55 per share as a final offer.

This tipped the valuation of the purchase to almost $70bn which the board of Pfizer felt would be too good to refuse as they had effectively paid a premium of 45% over the existing share price.

This tipped the valuation of the purchase to almost $70bn which the board of Pfizer felt would be too good to refuse as they had effectively paid a premium of 45% over the existing share price.

Some of Astra Zeneca institutional shareholders thought Christmas had come early and were tempted to take the cash and run.

However, from the point of view of the Astra Zeneca board and some of its leading shareholders, price wasn’t the only issue.

In situations like this, critical decisions are very often made on an emotional rather than purely rational basis.

So the ingrained perception of Pfizer as an asset stripper would’ve been eating away at the Astra Zeneca board as it evaluated its options. The evidence was compelling.

In 2000, Pfizer acquired Warner-Lambert for $90.3bn in stock. In 2003, Pfizer acquired Pharmacia for $60bn in stock and in 2009 it paid $68bn in cash and stock for Wyeth.

None of these deals had a happy ending and engulfed Pfizer in accusations that it simply stripped out patents, cut down research and development (R&D) and shut research facilities with consequent large job losses all in the pursuit of maximising profits and shareholder returns.

The board of Astra Zeneca clearly didn’t want to see the end of the company they’d worked so hard to create end up in much the same way as happened with Cadbury’s take over by Kraft. Its 6,700 employees would never have forgiven them and there was also a sense of pride as it accounted for three percent of all manufacturing exports from the UK.

Once the media machine cranked into action, it became a simple task to rattle the chances of the deal with headlines warning of higher drug prices for the NHS, thousands of redundancies and a brain drain from the UK.

Pfizer’s commitments to maintain research and jobs should it take over AstraZeneca were simply dismissed as “vague” and insufficient by the President of the Royal Society, Prof Sir Paul Nurse, whom I had the pleasure of working with as his head of communications in the mid ‘90s.

Pfizer’s commitments to maintain research and jobs should it take over AstraZeneca were simply dismissed as “vague” and insufficient by the President of the Royal Society, Prof Sir Paul Nurse, whom I had the pleasure of working with as his head of communications in the mid ‘90s.

Predictably, Pfizer’s CEO Ian Read was barbecued by the House of Commons Select Committee who were now suitably spooked.

And it probably didn’t help that Ian Read was less than convincing in his performance in front of MPs and even the Astra Zeneca board behaved more a like the unwilling bride of an arranged marriage.

“A more whole-hearted commitment would have gone far further than a price hike in getting the deal done,” adds Clive Rich.

“What if Ian Read had been prepared to say that Pfizer would make these commitments and give up shares if it failed to meet them but take more shares if it exceeded them?

“A real incentive for Pfizer to honour its targets might have created far greater reassurance, and simultaneously created even greater upside in the deal for Pfizer,” says Clive Rich.

Although it takes two to tango, the other party left anxiously looking on was the British Government that became increasingly nervous about the true intentions of Pfizer.

In the US, Pfizer paid corporation tax at the 35% rate whereas if they shifted to the UK as a result of the takeover of Astra Zeneca, the rate of corporation tax would drop to 20%, saving the company a whopping $80m a year.

Set against the recent backdrop of exposing aggressive tax avoidance schemes of companies such as Google, Amazon, eBay and Starbucks, the British Government didn’t want to be the unwitting partner of such a scheme.

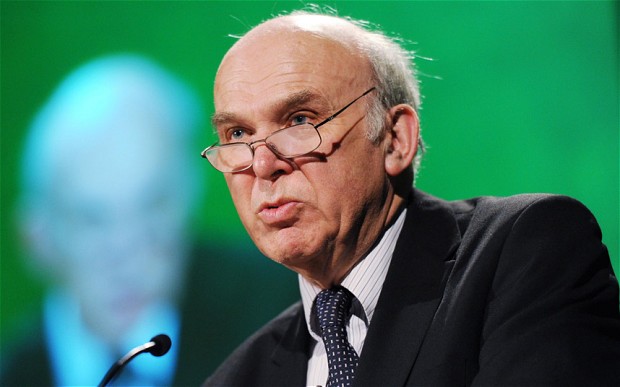

Business Secretary Vince Cable summed this up neatly when he said “we see the future of the UK as a knowledge economy, not a tax haven”.

Business Secretary Vince Cable summed this up neatly when he said “we see the future of the UK as a knowledge economy, not a tax haven”.

In the end price seemed to be the only instrument Pfizer was prepared to use to make the deal happen, and it failed to clinch the deal.

“As a drugs company Pfizer should’ve known that an addiction to anything may give you a high from time to time, but it doesn’t solve any of your underlying problems,” concludes Clive Rich.

So the moral of this story is that power, money and influence aren’t always enough to get a deal done.

Recent Comments