Choice is now something we all take for granted – from the type of product or service we desire, the features we look for that best suit our particular needs and requirements and even how much we’re prepared to pay for this.

Choice is now something we all take for granted – from the type of product or service we desire, the features we look for that best suit our particular needs and requirements and even how much we’re prepared to pay for this.

Traditional marketing thinking went something like this: “Increase levels of customer satisfaction and give customers more of what they want is the key to commercial success.”

Well, the reality is somewhat different in 2014.

Much of the time, most of us don’t think too deeply about how happy we are about the product we’ve just bought at the supermarket or the service we’ve received at the local shoe repairer or whether it completely fulfils our needs.

But now and again a new product will arrive on the market or we’ll find a more convenient service and we’ll switch without giving it a second thought even though we may have been “satisfied” with the old product or service for a long time.

So why does this happen?

The short answer is that our needs are never perfectly met, which in quality terms means that products and services never fully meet our needs and expectations. And of course our expectations tend to change with increasing regularity, possibly as a result of more choice.

The issue is as consumers or as a business, we can be “satisfied” with what we get from a company or supplier in terms of whether it matches with what we expect to get.

But that could still be accompanied by a deep sense that we didn’t really get just what we wanted and if someone else can provide this then we’ll shift our custom there.

In the past, “customer satisfaction” was thought to be what we expect to get less what we perceived we got. In essence, if our experience met or exceeded what we expected, then we were deemed to be “satisfied”.

But that’s a long way from claiming we received the product or service we actually wanted, isn’t it?

Customer satisfaction surveys fall into the same trap. These are OK at identifying the general needs or perceptions of desired customer segments but they often tell us very little about individual customer behaviour. They also tend to be reductive and as a result tell us very little about the unique group of individual customers’ wants and requirements.

As a marketer, if you rely on “customer satisfaction” as a key metric for brand performance, you’re in for a shock as you’re missing the bigger picture.

Definition of “customer sacrifice”

It’s now more accurate and profitable to think in terms of “customer sacrifice” rather than just pure “customer satisfaction”.

“Customer sacrifice” is defined as the gap between what customers need and what they accept.

My favourite example is the following: you find yourself on a flight and ask for a Diet Coke but are told by the flight attendant they only have Diet Pepsi.

My favourite example is the following: you find yourself on a flight and ask for a Diet Coke but are told by the flight attendant they only have Diet Pepsi.

It’s not the brand you drink but you accept the alternative. Let’s say you want to order a ham and cheese panini from the in-flight menu. When the flight attendant eventually gets to your seat, they advise you that they’ve sold out and all that’s left is cheese and tomato on white.

Reluctantly, you purchase the sandwich as you realise by the time you get to your hotel it will be too late to eat a meal.

Over the weekend, I had my own “customer sacrifice” moment when I was out with friends at a trendy restaurant in London’s Covent Garden and we ordered a couple of glasses of South African Chablis from the wine list.

The waiter came back with the drinks for everyone else but said they’d run out of what we’d ordered and simply offered the wine list again and we re-ordered something else.

The waiter came back with the drinks for everyone else but said they’d run out of what we’d ordered and simply offered the wine list again and we re-ordered something else.

I did ask how could they run out of wine as a restaurant? No explanation was offered and I did wonder whether I would come again as I wasn’t expecting to have made a “customer sacrifice” so early into our meal!

Mind the “customer sacrifice” gap!

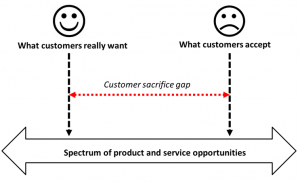

What happened on the flight and in the restaurant can be encapsulated in the following diagram:

The wider the “customer sacrifice” gap, the less chance of delivering customer satisfaction.

The wider the “customer sacrifice” gap, the less chance of delivering customer satisfaction.

In marketing terms, the “sacrifice gap” is an opportunity for competitors to better satisfy your customers and lure them away from you.

Of course it’s much more complex than this scenario as there may be a multitude of other variables that include quality, price and service attributes but the decision of the customer is likely to be a weighted aggregate of these “sacrifice gaps”.

Between the choices of two competing brands on offer, it could come down to that product which has the lowest sacrifice. This diagram sums up the challenge for marketers as the customer is settling for the best product they can find rather than what they really want.

The dangerous thing about this is that traditional customer research fails to reveal this situation as it tends to ignore the level of “customer sacrifice” a customer may have experienced in the first place.

New approach to customer research

Instead, “customer satisfaction” surveys tend to focus on how customers rate the company on a pre-defined series of categories.

As a result, “customer satisfaction” measurements essentially focus on understanding and managing customer expectations of what marketersalready do rather than trying to find out what customers actually want.

Marketers need to go beyond basic customer service metrics and develop a better sense of the perceptions of how much sacrifice your customers really feel with your product and supply chain services.

To some extent, Amazon is a great example of putting this into practice as it realises that timely delivery and fulfilment of orders is possibly even more important to the customer than the choice of products on offer on its website. The time between ordering and delivery is Amazon’s “customer sacrifice” moment and as reported in a previous blog it’s aggressively tackling this in order to compete with high street rivals.

But all is not lost.

Marketers should consider using online focus groups and surveys to detect “customer sacrifice” by exploring each element of the customer interaction that can provide clues about an otherwise unarticulated sacrifice dimension across which all customers settle for more or less what they want.

You need to seek answers to the following questions: What sacrifices – consciously or unconsciously – do your customers make when they accept your product or service? What assumptions do your customers make about what’s possible or not? What assumptions are you making about what’s possible and what’s not? What sacrifice does the market leader’s products and services require? How can you reduce “customer sacrifice”?

If you can see and cut “customer sacrifice” from your business you’ll be able to leap-frog your competitors and even enter new markets by becoming the challenger brand as this diagram illustrates:

Recent Comments