On the 18 September 2014 the Scottish people (pop. just over 5m) will make an historic decision. They will vote whether to remain as part of the United Kingdom or to separate from the union that has bound us together since the Act of Union 1707.

On the 18 September 2014 the Scottish people (pop. just over 5m) will make an historic decision. They will vote whether to remain as part of the United Kingdom or to separate from the union that has bound us together since the Act of Union 1707.

Historical background to this important referendum

This is probably one of the most important decisions that the Scottish people have had to make in the last 700 years. To understand the importance of this historic vote, it’s helpful to take a look at the events that happened over 700 years ago and in particular the Battle of Bannockburn.

Today, the Scottish town of Bannockburn lies immediately south of Sterling. It takes its name after Bannock Burn, a small stream running through the town before flowing into the River Forth.

Historians believe that this was the site for one of the most important battles in Scottish history.

On the 24 June 1314, the English King Edward II attempted to invade the country and turned up to fight King Robert Bruce who ruled Scotland. Despite the largest army ever gathered to invade Scotland with 2,000 horses and 25,000 soldiers, the Scots with 6,000 men were able to defeat the English invaders and Edward II fled back to London.

The English were led to believe that they could win but it was a masterful trick played by the Scottish King.

Seeing the Scots running into the woods, the English cavalry, led by Sir Henry de Bohun, gave chase and spotted King Robert Bruce. He thought this was his big chance to kill the Scottish King and claim victory over the country.

The Knight charged his horse with his lance drawn in the hope of killing King Robert Bruce, but the King side stepped the charge and brought his battle axe down on the knight’s head and striking him dead!

In this one act, King Robert Bruce had become a legend and forced the English to retreat.

The consequences of the Battle of Bannockburn lasted well over 400 years. King Robert Bruce had successfully held onto power and in doing so had protected the independence of Scotland from the ambitions of the English monarchy who wanted Scotland for themselves.

The consequences of the Battle of Bannockburn lasted well over 400 years. King Robert Bruce had successfully held onto power and in doing so had protected the independence of Scotland from the ambitions of the English monarchy who wanted Scotland for themselves.

On a more personal level, there was a prisoner exchange following the defeat of Edward II where English noblemen who were caught by the Scottish side were exchanged in return for the release of King Robert Bruce’s wife, daughter and Bishop Wishart who’d been held in prison since 1306.

The anti-English feeling was very deep and an example of this is 1320 Declaration of Arbroath that said the Scots would rather die than be ruled by England.

However, 400 years later, the situation would be very different.

1707 Act of Union

It was not until the rule of James I and VI (1566-1625) that Scotland moved closer to becoming part of the Union with England and Wales although it continued to remain an independent country.

The English were worried that Scotland would side with its old enemy France and also England passed the Act of Settlement 1701 that ensured England would remain Protestant.

The English were worried that Scotland would side with its old enemy France and also England passed the Act of Settlement 1701 that ensured England would remain Protestant.

However the Scottish Parliament passed its own Act of Security 1704 that said it would choose its own King. Not wanting to give up on the idea of a United Kingdom, the English used their influence, wealth and power to convince the Scottish Parliament that Union would be in their best interests.

On 22 April 1706, William Cowper, the Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, presented the Scots with the proposal that:

“The two kingdoms of England and Scotland be forever united into one kingdom by the name of Great Britain; that the United Kingdom of Great Britain be represented by one and the same parliament; and that the succession to the monarchy of Great Britain be vested in the House of Hanover.”

The Scottish Parliament agreed to take the historic step of union with England and Wales. On 1 May 1707 after much political and behind the scenes moves, the Scots passed the1707 Act of Union and Scotland became part of the United Kingdom.

“Yes” for Independence for Scotland

Should the Scots vote in favour of independence in the forthcoming referendum on 18 September this year, the 1707 Act of Union will be unravelled in 2014.

Should the Scots vote in favour of independence in the forthcoming referendum on 18 September this year, the 1707 Act of Union will be unravelled in 2014.

Not all political parties think Scotland should separate from the United Kingdom but the Scottish National Party (SNP) iscampaigning hard for such a result.

On its website the SNP describes itself as a “social democratic political party committed to Scottish independence. The party has been at the forefront of the campaign for Scottish independence for over seven decades.”

The party’s origins can be traced back over 100 years. In 1928, The Scots National League (formed in 1921) and the Glasgow University Scottish Nationalist Association (formed in 1927) combined with the Scottish National Movement to form the National Party of Scotland.

In 1934, the National Party joined with the Scottish Party to become the Scottish National Party. The turning point in the ambition for Scottish independence came when the Scottish Parliament met for the first time on 12 May 1999.

The 2007 Scottish Parliament and local government elections represented an opportunity for the SNP to become more influential in Scottish matters. They wanted to break the hold of the Labour/Lib Dem Parties on Scottish politics and campaigned on a promise to make Scotland more successful. In order to attract votes, the SNP promised to support vital health services; support small business; protect communities; and reduce taxes for people. The party was also one of the first to use social media to get their messages across to voters. The plan paid off and the SNP became the largest political party in terms of votes and number of MPs elected to the Scottish Parliament, known as MSPs.

Main arguments for independence

The SNP have set out their arguments for an independent Scotland in what’s known as a manifesto.

The main argument made by Scottish nationalistAlex Salmond MSP, First Minister of Scotlandis summed up in this quote: “It’s fundamentally better for all of us if decisions about Scotland’s future are taken by the people who care most about Scotland – that is by the people of Scotland. It’s the people who live here who will do the best job of making our nation a fairer and more successful place.”

- Scotland can afford to go it alone because it receives more money in taxes compared to the rest of the UK and has saved over £19bn over the past 30 years.

- Scotland can borrow a lot of money because of the investment made in drilling for North Sea oil and gas that is worth £1tr and will earn the country £54bn over the next five years.

- Scotland is one of the countries in Europe that is leading the way in alternative energy such as wind and tidal power that could be worth £14 billion each year.

- Key growth businesses that will earn money for Scotland in the future include:tourism; food and drink; whisky; financial services; engineering and scientific research in health and diseases.

- Scotland will get its own currency and will be able to help families by reducing fuel and energy costs.

- Decisions about the future of Scotland would no longer be decided by MPs in theWestminster, for example getting rid of nuclear weapons.

- More jobs for Scottish people in running their own country.

- A new Scottish passport would be created for those who are born in Scotland.

Betting shops in Rosyth are rowdier than usual, reports The Economist. The troublemakers aren’t the familiar sort—drunks jousting over a Rangers match or the 4.30 at Musselburgh—but punters debating Scottish independence.

“We’ve had to chuck people out,” grumbles one bookie.

A gnarled customer agrees: “I don’t like people talking about it in my cab,” he growls, eyes not moving from the racing. As the referendum on September 18th draws closer, tensions in this shipbuilding town are growing.

All politics is local, even when an entire country’s future is at stake. But in Rosyth, a run-down port in the shadow of the Forth Bridge near Edinburgh, distinctive local factors are pulling people in opposite directions. The importance of the town’s biggest industry seems to militate for sticking with the union.

But the generally depressed state of the economy makes independence more appealing. The outcome of this tug-of-war will determine how people vote in Rosyth—and in other parts of Scotland. Residents are reminded of the case for union every time they leave their homes.

Above treetops and through gaps between pebble-dashed houses, glimpses of a vast blue rig marked “Air Carrier Alliance” and “Royal Navy” are visible.

Beyond, the grey, 65,000-tonne slab of Britain’s newest aircraft-carrier, HMS Queen Elizabeth, sits in the estuary. In a place where 13% of working-age adults are on out-of-work benefits, the shipyard is by far the largest employer—and it relies on money from Westminster.

Beyond, the grey, 65,000-tonne slab of Britain’s newest aircraft-carrier, HMS Queen Elizabeth, sits in the estuary. In a place where 13% of working-age adults are on out-of-work benefits, the shipyard is by far the largest employer—and it relies on money from Westminster.

Those who build and man the ships are therefore firmly unionist. And who can blame them?

At a ceremony to name the carrier on July 4th, they heckled Alex Salmond and the following week the Rosyth workers’ union representatives appeared before MPs in Westminster to warn against secession.

Henry Wilson, a convener at BAE Systems, a defence firm, warned that naval shipbuilding in Scotland would be “finished” if Alex Salmond got his way.

Main arguments against independence

There are several campaigns that argue for maintaining Scotland as part of the United Kingdom. For example, the ‘Better Together’ campaign that’s supported by Harry Potter author JK Rowling talks about giving more power to the Scottish Government to make decisions for itself.

There are several campaigns that argue for maintaining Scotland as part of the United Kingdom. For example, the ‘Better Together’ campaign that’s supported by Harry Potter author JK Rowling talks about giving more power to the Scottish Government to make decisions for itself.

Other campaigns talk about the need for Scotland to remain a partner of the United Kingdom in order to have a brighter and more secure future for the Scottish people. An important argument made by the “No” campaigners is that Scotland will face an uncertain future if it broke away from the United Kingdom.

All three major political parties – Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats – have joined together to argue in keeping Scotland as part of the United Kingdom. In a booklet, the “No” campaigners warn voters that the decision taken in the referendum will be irreversible and there’ll be no going back. They argue that voters should think very carefully about the decision before the vote.

The main arguments made by the “No” campaigners is summed by this quote by former Prime Minister Gordon Brown who himself is a Scot: “Independence may be a big idea but I believe my vision of Scotland’s future, sharing risks and resources across four nations, is a far bigger idea and a more compelling vision for the integrated and interdependent world of the twenty-first century than separation.”

- As part of the United Kingdom, Scotland will continue to enjoy being part of a very strong economy within Europe

- The Pound is one of the most trusted and stable currencies in the world. If Scotland were to leave the UK, it would cause problems for people buying goods and services within the rest of the UK

- Creating a new currency that has never existed before may make a lot of people very worried

- The cost of borrowing money will increase and buying a house or flat in Scotland could become unaffordable for many people

- Many businesses will increase their prices for shoppers as they feel it’s more expensive to do business in Scotland and have kept prices the same for all shoppers until now

- Scotland will miss out on money invested in the UK if it becomes a separate country

- Jobs are at risk as many large companies are planning to move their main offices out of Scotland if it becomes an independent country

If the Scots vote “No” to independence, then all three major political parties have promised to give more power to the Scottish Government in order for it to raise taxes and also make more plans and policies that directly affect Scottish people and the future of Scotland.

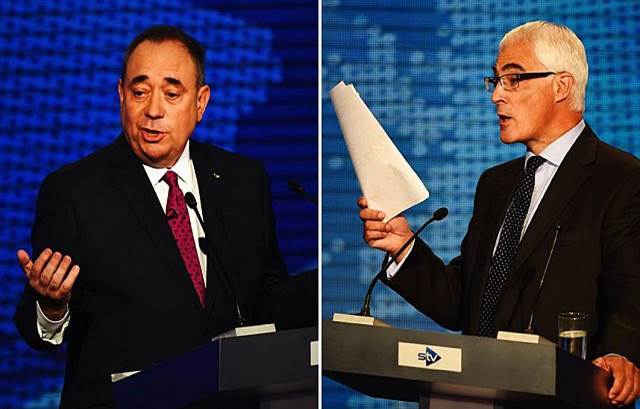

With just a little under six weeks to go before the big vote, Alistair Darling MP clashed in a sometimes heated debate with Alex Salmond before a live TV studio audience.

Alistair Darling, who was Chancellor under Gordon Brown’s Labour Government, repeatedly pressed Alex Salmon on his plan ‘B’ if Scotland failed to secure a currency union to allow it to retain the pound in the wake of a “Yes” vote.

Alex Salmond didn’t have an adequate response for this and an ICM poll conducted in the wake of the TV debate with 512 people showed the majority (51%) sided with the ‘No’ argument and just 40% of respondents were in the “Yes” camp.

What’s the likely outcome?

A number of recent polls, including that of YouGov, show that the “No” campaign is well ahead and it’s held this lead for some months.

Unless things change markedly in coming weeks, I believe Scotland will vote to remain in the United Kingdom and by a decisive enough margin to settle the matter for many years to come.

Back in Rosyth, one drinker in the ex-servicemen’s club on Admiralty Road is willing to admit to backing the “Yes” campaign.

“Ey, I’ve made up my mind,” says Jimmy, grinning defiantly. He struggles to hold his own around here, he adds: “full of “No” voters; gets very heated.”

“He won’t listen,” sighs Janet, the barmaid, wiping beer glasses. Janet thinks Alex Salmond’s promises are baloney: “I don’t trust him as far as I could throw him.”

Jimmy is in a minority in the ex-servicemen’s club, but he may not be in Rosyth at large.

Nationalist sentiment is widespread. More “Yes” signs are visible in windows than are “No” ones. Scottish saltires the size of bedsheets billow above allotments and from blocks of flats. Beyond the shipyard there is little sign of the British union flag.

In 2010 an NHS study of central Rosyth put male life expectancy at 73.3 years—five years shorter than the British average. Teenage pregnancy and welfare dependency are unusually common, too. Those hard-up locals not employed in the shipyard could be forgiven for thinking that the union isn’t working for Scotland—and taking a gamble on independence.

In 2010 an NHS study of central Rosyth put male life expectancy at 73.3 years—five years shorter than the British average. Teenage pregnancy and welfare dependency are unusually common, too. Those hard-up locals not employed in the shipyard could be forgiven for thinking that the union isn’t working for Scotland—and taking a gamble on independence.

A great many former Labour Party voters fall into this category. The collapse of the party’s working-class base in the 2011 Scottish election gave SNP the majority it needed to press for a referendum on independence. In Cowdenbeath, the seat containing Rosyth, support for the SNP jumped from 29% to 42%.

This makes Rosyth typical of a sort of Scottish town: post-industrial and deprived but sustained by the British state, which spends about £1,500 ($2,500) more per head in Scotland than it does nationally.

Others include Govan and Scotstoun, both shipyards, and Pollokshaws, home to National Savings and Investments, a state-owned bank. In Cumbernauld, outsideGlasgow, Britain’s largest revenue and customs office employs four times as many people as any other outfit.

Gregg McClymont, Labour MP for Cumbernauld, notes that Scotland has 8% of Britain’s people but 13% of its tax jobs. How could it sustain them if it became independent?

In such places, the “Yes” campaign faces a particularly acute version of a problem that confronts it across Scotland. The disadvantages of independence are concrete and would be quickly felt—in the case of Rosyth, shipbuilding jobs would sail to Portsmouth, on England’s south coast.

Any advantages, such as the broad industrial revival promised by Alex Salmond would take years to materialise, if they ever do.

Folk in Rosyth enjoy the odd flutter. But on September 18th the stakes will be much higher than usual.

Recent Comments